왜 熱帶學 공부인가

Why Tropical Studies Matter

I.

서구적 근대가 만들어놓은 동양 대 서양의 이분법 틀에

갇혀 있으면,

어떻게

열대의 대지를 만질 수가

열대의 질감을 맛볼 수가

열대의 소리를 들을 수가

열대의 빛과 색을 볼 수가

열대의 냄새를 맡을 수가 있을까?

‘나는 생각한다. 그러므로 존재한다.’에서 출발하여 합리성의 정점에

도달한 이성 중심의 서구 세계관은 열대의 생물지리적 탐험을 통한

시각적 공간화, 공간적 시각화와 맞물려

근대적 욕망을 발명했다.

책머리에 향료, 설탕, 커피, 차, 담배 등을 더 많이 차지하기 위한

욕망과 충족의 대위법은

열대의 무역과 통상, 식민화, 그리스도교화, 문명화, 청결화의

다섯 층위를 통해 서구적 근대의 매트릭스에 내장되었다.

고대 그리스-로마로부터 젖줄을 이어받으면서

인류 문명의 이름으로 발달시켜갔던

근대 학문과 예술은 열대를 은폐시키면서

서구적 근대의 형식과 내용을 더욱 정교한 방식으로 정당화했다.

과학혁명, 산업혁명, 프랑스혁명, 미국혁명.

서구 인류사 중심의 혁명 이야기는 목청껏 노래를 부르면서도

아이티혁명은 기껏해야 바람처럼 스쳐지나 갈 뿐이다.

더욱 근본적으로 ‘자연사혁명’은 서구 히스토리오그라피에서

찾아볼 수 없다. 열대 자연사가 은폐되었기 때문이다.

서구 인류사의 혁명적 전환기에서

뷔퐁, 칸트, 헤르더, 뱅크스, 괴테, 알렉산더 훔볼트는

자연사와 인류사가 분리되어갔던 시기에

낭만주의와 어우러진 역사지질학적 상상력을 통하여

양자를 소통시키려고 절치부심했지만

열대 자연사의 본질을 꿰뚫을 수 없었다

1808년 성탄절을 앞두고 두 교향곡이 한 장소에서 초연되었다.

6번 : 5번 = 자연사 : 인류사

베토벤은 서구의 사상가들과 역사지질학의 문제의식을 공유했기에

〘전원교향곡〙을 먼저 연주했으며

베를린 필의 지휘자 푸르트뱅글러도 베토벤을 좇아

전원을 먼저 연주하면서 불멸의 음반을 남겼다.

제국주의가 절정으로 치닫고 있던 시기에

오감의 열대성을 문학과 미술로 형상화했던

조셉 콘라드, 폴 고갱, ‘세관원’ 루소의 작업은

서구 정체성의 경계를 넘어서기 위한 몸부림이었다.

인문학, 사회과학, 자연과학은 서구적 근대의 지적 소산이다.

태생적으로 서구적 근대는 열대 자연사를 통해 형성되었지만

근대 학문과 예술은 열대를 은폐시켰다.

그 이유와 과정을 탐구하게 되면,

인류세에 관한 문제의식을 풀어갈 수 있는

해법이 열대 자연사에 있음을 인식하게 될 것이다.

II.

‘조선의 태양은 중국에서 떠서 중국으로 진다.’

중화(中華)와 소중화의 그물에 얽매여 있으면,

‘문화융합’이

열대 아시아, 아프리카, 아메리카

인도양, 대서양, 태평양에서

어떻게 이루어지고 있는지를 알 턱이 없다.

광활한 바다를 열대 해양력의 힘으로 건너온

네덜란드동인도회사가 무역과 통상의 손길을 건넸을 때

‘우리에게는 모든 것이 있으니 필요한 것은 하나도 없다.’

조선왕조는 그렇게 말했다.

‘모든 길은 옌칭으로’ 향했던 사회에서

유럽과 미국의 무역회사들이

광저우에서 무엇을 하고 있는지

강남갔던 제비가 어떻게 소식을 물어오겠는가!

조선통신사는 네덜란드가 나가사키에서

무역을 한다는 것에 대해 들어서 알고는 있었다.

그러나 조선왕조는 그것이 열대 해양무역 네트워크에서

빙산의 일각이라는 사실을 알지 못했다.

‘황사영 백서’의 핵심은 천주교가 아니라 예수회이다.

전지구적으로 열대에서 ‘한 손에 성경,

다른 한 손에 무역’ 행위를 했던

예수회의 본질을 간파하지 못했다.

‘홍어장수’ 문순득이 마닐라, 광저우, 마카오에서

스페인, 아메리카, 필리핀을 연결하는 갤리언 해양무역과

서구 ― 동남아시아 ― 중국 ― 일본을 잇는 해양무역에 대해

정약전에게 말했지만 그는 기록으로 남기지 않았다.

소중화의 문화역사지리적 경계를 넘어서기가 두려웠고 어려웠다.

조선 실학의 담론이 문제가 아니다.

문제는 성리학 대 서학이 아니다.

문제를 자연사의 지평에서 문제화하기.

자연사 중심의 시각적 사유가

조선에서는 왜 억압이 되었는가.

열대 동남아시아 문화역사지리의 중심

아유타야왕조와 교역을 할 수 있던 힘이 있었기에

일본은 네덜란드를 통해 서구적 근대를 배워갈 수 있었다.

이순신의 해양군사력을 더 이상 발달시키지 못했던 한양은

소중화의 깃발을 높이 쳐들면서 바다 대신에 대륙으로 향했다.

서구와 열대 사이에 이루어졌던 식민적 문화융합에 대해

조선 권력이 무감했던 이유는 무엇일까.

‘을사늑약’ 이후 난생 처음으로 타보는 일본 기차에서

담배를 피우며 상념에 잠겼던 《일동기유》의 김기수 마음은

〘비 증기 속도〙를 그리면서 영국의 앞날을 고민했던

윌리엄 터너와 어떻게 달랐을까.

세계냉전체제에서 작동했던

분단의 검열 장치와 근대국가 건설은

서구적 근대를 강요했고 열대의 오감을 억압했다.

천경자는 과학적 학습이 아닌 예술가적 직관으로 이를 감지했다.

‘아프리카 중에서 아프리카’인 콩고에서,

레비스트로스에게 열대 자연사의 상상력을 촉발시켰던

콘라드의 《암흑의 심장》과 동심원의 통찰력으로,

〘내 슬픈 전설의 49페이지〙를 그리면서

‘아프리카를 보고 죽어라!’고 주문을 외웠다.

‘동양화를 동양적인 것으로 합리화’하지 않으려는 그의 의식은,

조선에 가위눌린 국악을 넘어서기 위해

신라의 상상력을 통해 〘沈香舞〙를 작곡했던

황병기와 공명을 울린다.

자연사의 원리이니 기억하자.

개체발생은 계통발생을 반복한다.

보릿고개도 넘기 어려웠던 한국이 국제개발협력의 이름으로

열대의 가난한 나라를 원조할 수 있게 되었다.

지난 5백년간 서구와 열대의 식민적 문화융합 역사에 대해

깊이 성찰하지 않은 채로

민주화의 역사는 배제한 채로

산업화의 경험만으로 국제개발협력에 나선다면

열대에 대한 신식민주의와 다를 바가 없다.

마다가스카르의 한국 기업들이 보여준 플랜테이션 산업은

이를 여실히 증명하고도 남지 않는가.

III.

삼백년간 서구가 열대를 은폐하면서 만들어갔던 근대를

한국인은 삼십년간 압축 실행했다.

어느 시인의 말대로

“삼십년에 삼백년을 산 사람은 어떻게 자기 자신일 수 있을까.”

역사적으로 중국과 일본에 이어 미국이 한국의 중심이 되었다.

다음은 중국으로의 회귀인가.

아프리카 대륙을 토목공사판으로 만들고

라틴아메리카를 식량농업을 위한 신제국주의적 플랜테이션으로 만들고

남태평양을 해양산업의 안보기지로 만들어가는

중국이 통일 한국의 새로운 모델이 결코 될 수 없다.

한국 대학의 수직적 분과 학문체제로는

서구적 근대를 추종하는 데도 숨이 찰 지경이다.

그런데도 지식권력은 기득권을 포기하지 않는다.

서구적 근대가 시작된 유럽은 융합으로 가는데

정작 이를 허겁지겁 수용한 한국은 분과 학문의 철옹성이다.

인류사 중심의 학문과 예술의 경계를 넘어

열대 자연사와의 융합을 통해 숙성된 열대학으로 나아가자.

자연사와 인류사의 관계를 혁명적으로 변화시켜야 한다.

열대학의 문화역사지리적 상상력으로

아프리카, 동남아시아, 남태평양, 라틴아메리카와 문화융합하자.

한국 사회 전체를 옥죄면서 다가오는 ‘인구절벽’은 절박하게 외친다.

열대와 전지구적으로 문화융합하라!

용인 신봉동에 수령 삼백년이 된 느티나무와 함께 하면서

저자 씀

INTRODUCTION

The main crux of my argument is that the Western humanities, arts and social sciences have hidden the fact that Western modernity was formed and established through its colonial transculturation with the tropics on a global scale. Representing much more than merely the geographical zone between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, ‘the tropics’ in my thesis refers to the complex of cultural, historical and geographical space that has been constructed by the West since the encounter between the Old and New World. The tropics is an essential concept in recognizing how natural history has been oppressed by Anthropocentrism in historical studies. While emphasizing that the world consists of the East and the West, mainstream Western-centric historiography has obscured the tropics as a crucial source of Western identity. The natural history of the tropics has been reduced to a history of Westerners through their natural resources exploitation for economic development in the tropics as well as in the West and the East. Even environmental history fails to fully illuminate the tropical basis of Western modernity. Therefore, from the integrative perspective of natural and human history, I ask foreign readers to re-think Western anthropocentric scholarship and arts in the context of Western colonial transculturation with the tropics. It is no coincidence that a fully-fl edged Western modernity and the Anthropocene began simultaneously in the second half of the eighteenth century. Western colonial transculturation with the tropics was entwined with anthropogenic forces on African slave labor, American plantations and Asian natural history products. I propose that future research on the tropics - what I term ‘Tropical Studies’ here - should no longer be reduced to isolated regional studies in Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America and the South Pacifi c. ‘Tropical Studies’ is not merely the sum of regional studies of the tropics, but rather it is an integrative fi eld inclusive of the humanities, the arts, the social sciences, the natural sciences and medicine. I hope that Tropical Studies will become tremendously signifi cant in the epoch of the Anthropocene.

METHODOLOGY

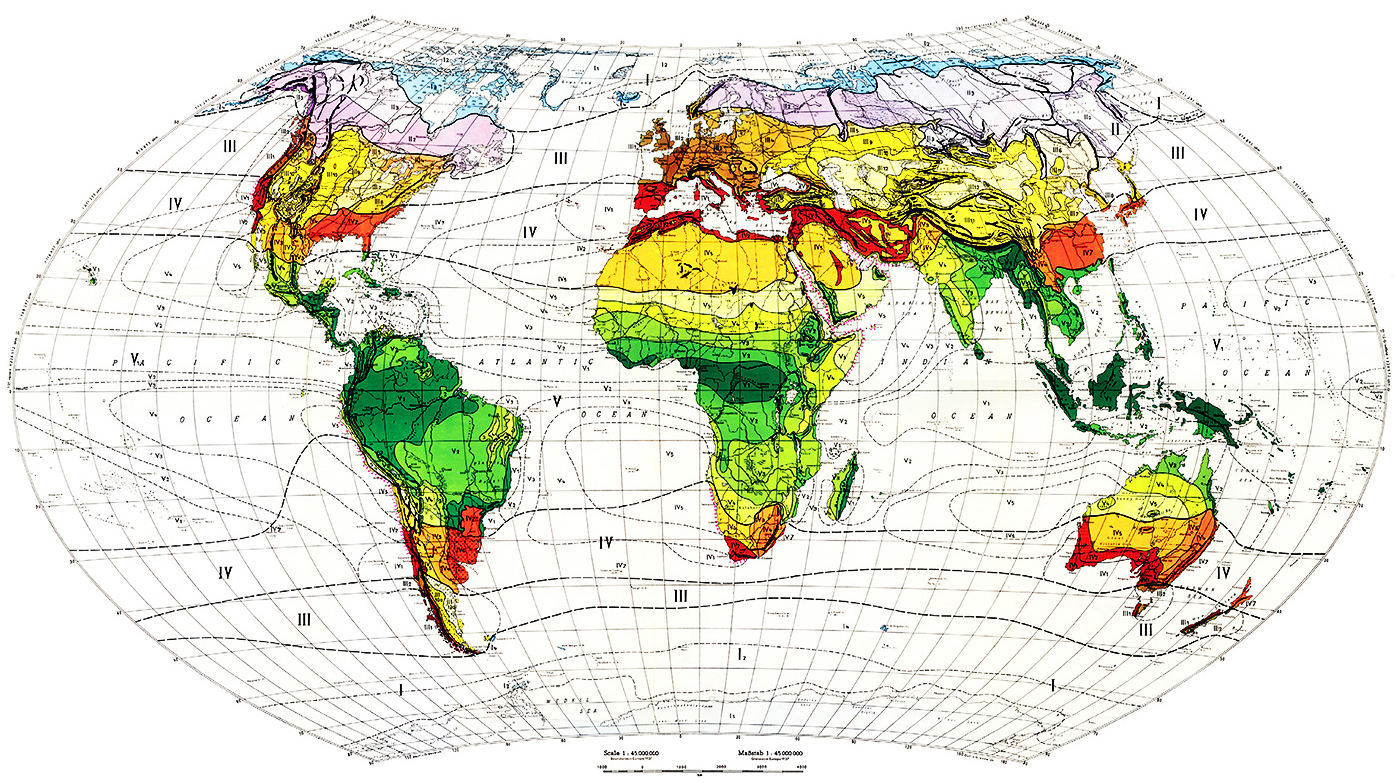

My research on the tropics was highly piqued by reading the works of the following thinkers and scholars: Alexander von Humboldt, for an integrative perspective on human and natural history through biogeographical exploration; Sidney Mintz, for a historical anthropology of sugar plantations in the Caribbean islands; Philip Curtin, for a history of European encounter with Africa; Claude Levi-Strauss, for a natural history of the tropics; Fernando Ortiz, for a historical sociology of transculturation in colonial Cuba; Leonard Blusse, for the encounter between Europe and tropical Asia; Bernard Smith, for a European vision of the tropics; Martin J. S. Rudwick, for a historical geology of the Earth; Steven Jay Gould, for an evolutionary biology of the species; Clarence J. Glacken, for a historical geography of nature; Gilberto Freyre, for ‘tropicology’ in Brazil; William J. T. Mitchell, for an iconology of landscape painting; Paul J. Crutzen, for the Anthropocene, and Lawrence Joseph Henderson for the unifi cation of natural and social sciences. In addition, I conducted a number of ethnographic interviews with many elderly persons in a variety of places in the tropics such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Uganda, India, Borneo, Indonesia, Cambodia, Cuba, Peru, Mexico, the Amazon, and Brazil. Having actively participated in numerous academic conferences held in Europe and the U.S., I have taken an advantage of conference-free time to visit many European botanical gardens, zoos, and natural history museums for the fi eldwork. Alternating visits to the tropics with stays in the West enabled me to recognize the pivotal role of the tropics in the making of Western modernity. Furthermore, a variety of tables, maps and illustrations are included in the book not only to help readers understand my arguments but also to encourage them to interpret these visual images. Visual thinking is pivotal to understanding the tropics in the making of Western identity

STRUCTURE

In Part I, I contend that Western identity is based on fi ve building blocks: commerce and trade, Christianization, colonization, civilization, and cleanliness. These blocks have been historically inseparable from the tropics. In addition, the driving forces of Western modernity consist of three components: tropical sea power and military forces, biogeographical exploration of the tropical natural history, and maritime trade with the tropics. Nevertheless, Western modernity has focused on Western-centric human history revolutions such as the Scientifi c Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution, and the American Revolution. Even the

Haitian Revolution is absent from the natural history of the tropics. In an era of revolutionary changes in Western history, ‘great’ thinkers such as Georges Buff on, Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottfried Herder, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Joseph Banks, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Alexander von Humboldt relied upon the historicalgeological imagination to illuminate the relationship between natural and human history. However, nobody conceptualized the ‘Natural History Revolution,’ because they never considered the Haitian Revolution in relation to a natural history of the tropics. I investigate the Haitian Revolution in terms of the natural history revolution

that originated from complex interactions between African slaves, American plantations, and European colonization of the tropics. As the West invented its modern desire for spices, sugar, coff ee, tea, and tobacco through trade with the tropics, it also began to demand the scientifi c disciplines and practical methods necessary to civilize, Christianize, cleanse, and colonize the tropics. It was through colonial transculturation between the West and the tropics that a variety of concepts, theories, and methods were formulated in the modern social sciences. I explore how such concepts that have underlain sociology, economics, anthropology, psychology, and

demography derived from Western colonial transculturation with the tropics.

In Part II, contrary to existing views of Western modernity, I argue that European explorations of the tropics triggered literary and visual representations of the tropics. Such representations were transformed into the invention of modern desire for tropical products. To satisfy these desires, the fi ve aforementioned building blocks were institutionalized through Western colonial transculturation with the tropics. I emphasize that this institutionalization was set up through reciprocal interactions between the tropics and the West, rather than being established initially in the West and only subsequently in the tropics. The colonial production of tropical

space is deeply intermingled with the satisfaction of modern desire. Several pioneers are investigated in relation to tropical natural history exploration: Christopher Columbus; Ferdinando Magellan; Jean de Lery; Carl Linnaeus and his ‘disciples’; Joseph Banks; Alexander von Humboldt; Alfred Wallace, and Charles Darwin. Exploring Romanticism from the perspective of a natural history of the tropics leads us to reject common misconceptions of it as a solely Western artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement. Romanticism is not an exclusively Western legacy but rather an intellectual product of colonial transculturation between the West and the tropics.

Existing literary and artistic critiques that seek to understand Romantic novels and arts have masked tropical natural history. A tropics-oriented reading of Western humanities and arts from the late 1700s through the early 1800s reasoned me to contend that Romanticism resulted from European colonial transculturation with tropical natural history. I focus on several specifi c works of European novelists and artists to analyze how the tropics shaped both the form and contents of Western identity: Bernardin de Saint-Pierre; Robert Thornton; Joseph Conrad; Paul Gauguin; Le Douanier Rousseau; Michel Tournier; JeanChristopher Rufi n, and the two Nobel laureates,

Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio and John Maxwell Coetzee. Based on these analyses, my thesis is that, so long as Western literature and arts continue to obscure the natural history of the tropics, we cannot recognize the true meaning of Western identity and modernity. Many Korean readers may wonder why and how Tropical Studies matters in Korea, which does not belong to the tropics. I therefore discuss the case of Korea in Part III, which also provides foreign scholars of Korean Studies with an alternative perspective to enhance their scholarships. It examines the Kingdom of Joseon (朝鮮, 1392-1910) in the context of global maritime trade with the tropics and

analyzes contemporary Korean transculturation with the tropics. Several kingdoms before the Joseon dynasty had long maintained maritime trade relationships with tropical Southeast Asia, mostly through Chinese trade cities. However, this tradition was abruptly abolished after the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) diplomat and explorer Zhenge He conducted seven maritime voyages to the Indian Ocean (1405-1433). Since the Qing dynasty’s (1644-1912) domination of China, the ruling class of the Kingdom of Joseon saw itself as the center of the world and dismissed the Qing as ‘barbarians’. Although the Dutch East India Company seriously tried to trade with the Joseon dynasty, the

so-called ‘Sojunghwa’ (小中 華) - an ideological Confucian variant of Sino-centrism (中華) - led the dynasty to have no interest in cultural and trade relationship with the Netherlands. The Kingdom was isolated by itself from surrounding countries. Even some reform-minded ‘Silhak’ (實學) scholars, who tried to accept ‘Seohak’(西學, literally meaning ‘Western learning’), did not explore how the Joseon dynasty could be incorporated into the global maritime trade network with the tropics. Over the last seventy years, Korean society has trodden the development paths set out by Western modernity. Indeed, Korean humanities, arts and social sciences are so much based on

the U.S. model that Korean intellectuals do not try to recognize that the tropics has been hidden in Western scholarship. However, a few Korean thinkers did try to recognize the signifi cance of the tropics in an era of globalization; I analyze their works and eff orts in the context of Korean transculturation with the topics. Korea had been a recipient of Offi cial Development Assistance (ODA) since the Korean War (1950-1953). However, in 2010, Korea surprisingly became the 24th member of the Development Assistance Committee, the international donors’ club. This turning point in the history of Korea’s international development raised a very important question:

what kind of ODA programs should Korea provide for the tropics? Readers will remember that Sub-Saharan Africa still suff ers from severe poverty and many tropical diseases despite being a long-term recipient of ODA from the West. Thus, Korean people should critically evaluate the Western model of modernization from the perspective of Tropical Studies. To go beyond ‘Korean Orientalism’ on the tropics, Korean intellectuals must fi nd out how the humanities, arts, and social sciences have hidden the tropics in the making of Western identity.